by Raza Kawsar

During my learning of German and constant practice of English for my thesis, I noticed that the same concept, depending on the language used, influences the mental image and perception of the idea [1]. This led me to ask questions: how does language influence perception and cognition? How does language shape our perception of the world? Is one language more suitable than another for inspiring new ideas? Out of curiosity and for my personal understanding, I became interested in this subject and looked up studies conducted in this area.

The words we use to learn and transmit knowledge profoundly shape our understanding and our ability to conceptualize abstract ideas. Language, as a communication tool, is not neutral; it carries cultural, cognitive, and emotional biases that influence how we interpret and integrate new information [2].

Semitic languages often use metaphors to express abstract ideas, while Western languages rely more on rational and comparative concepts. Metaphors are not just stylistic tools but powerful cognitive frameworks. For instance, learning physics through analogies like “electric current is like water flowing in a river” can make abstract concepts more accessible [3].

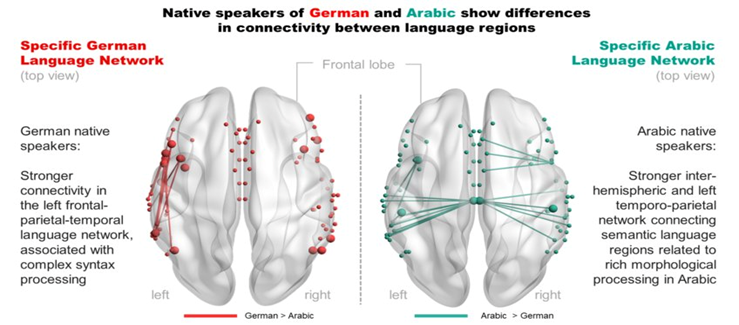

Some languages favor specific thinking structures. For example, languages like French and German, with their grammatical complexity, can influence the rigor and precision with which ideas are formulated and understood. One of the recent articles [4] I read discusses how neural connections differ based on the language spoken. Much research is being conducted in this field to understand how language modulates brain networks [5].

It is possible that because of our thinking, we do not truly live in reality but rather in a kind of mental hallucination constructed from the activity of our thoughts. This idea of living in a mental delusion is disconcerting. How can we then see reality objectively, and how can we grasp reality without being biased by these illusions [6]?

We can also question whether there is a perfect language, in which the meanings of words remain unchanged over time. What would the grammar of such a language be? Could, for example, programming languages be a substitute for a living language? These questions are all the more relevant with the rise of AI.

Understanding the impact of language on learning involves choosing words and structures that facilitate not only comprehension but also inspiration and innovation. By exploring these aspects, we can better understand how language shapes our learning and, ultimately, our worldview. Unfortunately, I cannot delve further into the topic. I invite interested readers to pursue their reading through the articles cited in the references.

References

[1] Stanislas Dehaene, The Number Sense: How the Mind Creates Mathematics, British Journal of Educational Studies, 47(2): 201-203, 1999

[2] Edward Sapir, Selected Writings of Edward Sapir in Language, Culture and Personality, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1949

[3] Benjamin Lee Whorf, Language, thought, and reality: Selected writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf, MIT Press, 2012

[4] Xuehu Wei et al, Native language differences in the structural connectome of the human brain, NeuroImage, 270: 119955, 2023

[5] Rachel R. Romeo, Beyond the 30-Million-Word Gap: Children’s Conversational Exposure Is Associated With Language-Related Brain Function, Psychological Science, 29(5):700-710, 2018

[6] Gary Lupyan and Emily J. Ward, Language can boost otherwise unseen objects into visual awareness, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(35):14196-14210, 2013